- Visual

Thinking

- Visual

Thinking--the Highest Sense

- Theoretical

Thinking

- Visual

Dynamic

- Homeostatic

Equilibrium

- Entropy

- On

Photography

- Outside

In--Environment-Driven

- Limitations

of Visual Dynamic

- Natural

Accident

- Particularity

- Paralyzing

Expression

- Conclusion

- References

How is the

psychology of art related to photography? When I mention the psychology

of art, many people may think it is a type of experimental psychology

that studies human perception of color and composition, which would

seem to have a natural connection to photography. Interestingly enough,

the arguably most well-known psychologist of art, Rudolf Arnheim, is

not an experimental psychologist. With the exception of his

dissertation and one or two other writings, he has never published an

experimental study (Verstegen, 1996). Instead, throughout his career he

has "philosophized" a psychology of art. Arnheim, a German immigrant to

America, studied psychology at the University of Berlin during the

1920s. At that time psychology was considered a branch of philosophy

(Behrens, 1998).

During

Arnheim's career, he wrote 15 books and numerous papers on the

psychology of art. He conducted research and taught in major American

universities such as Columbia and Harvard. In addition, he served twice

as the President of the American Society for Aesthetics, and served

three terms as the President of the "Division on Psychology and the

Arts" of the American Psychological Association. The fact that Arnheim

is such a prominent figure in the study of art makes his criticism of

photography especially problematic. I hope that this article can give

photographers sufficient knowledge to critique Arnheim's viewpoint.

The objective

of this article is to introduce and criticize Arnheim's

"philosophical/psychological" view of photography. To comprehend his

view of photography, a general overview of his psychology of art is

essential also. "Dynamic" expression is the theme of Arnheim's theory.

In his theory, the more visual tensions an artist presents, the more

dynamic expression the work carries. Arnheim believes that photography

is not as dynamic as painting because photography is too

environment-driven to grasp the essence of a subject or express the

authentic personality of a model. In the following, I will outline the

fundamental concepts of Arnheim's theory and give a brief critique to

some of his views.

The pursuit of

logic and rationality prevails in Western culture. Arnheim (1974)

asserted that Western culture is "unsuited to the creation of art and

encourages the wrong kind of thinking about it. We have neglected the

gift of comprehending things through our senses. Concept is divorced

from percept, and thoughts move among abstractions." (p.1) He insists

that visual thinking cannot be conveyed by verbal language. For

instance, the entire experience created by a Rembrandt painting could

not and should not reduced to description and explanation (pp.1-2).

Arnheim

(1979) agrees with philosopher Wittgenstein that words are like the

skin of a deep water, [so] we must penetrate beneath the skin. And

Arnheim even goes further to claim that humans' highest sense is the

sense of vision (p.146). Moreover, Arnheim (1986) is opposed to the

notion that intuition is just artists' effortless inspiration while

intellect is a kind of serious logical thinking. Actually, he says,

intellect is a linear or sequential analysis, while

intuition is a synthesis of the entire structure.

Intuition enables us to perceive and interpret the relations between

various elements of a subject (pp.13-30). *

Fortunately,

Arnheim does not go to the extreme to exclude conceptual thinking from

artistic activities. In Arnheim's view (1969), intuition or visual

thinking is by no means a sufficient condition for artistic creation.

Genuine artwork requires organization, which involves many, and perhaps

all, of the cognitive operations of theoretical thinking (p.263).

Perceptually, a mature work reflects a highly differentiated sense of

form, capable of organizing various components of the image in a

comprehensive compositional order. The intelligence of the artist is

apparent not only in the structure of the formal pattern, but equally

in the depth of meaning conveyed by this pattern (p. 269).

In brief, the

work of art is an interplay of vision and thought.

The individuality of particular existence and the generality of types

are united in one image. Percept and concept are revealed as two

aspects of one and the same experience (p.273).

Arnheim

(1988, Nov.- Dec.) asserts that the world of sensory experience is not

made up of things, but of dynamic force. The key to expression in

visual art is the rendering of dynamic forces in fixed images.

Expression is the manifestation of life, and life is what art is all

about (p.585).

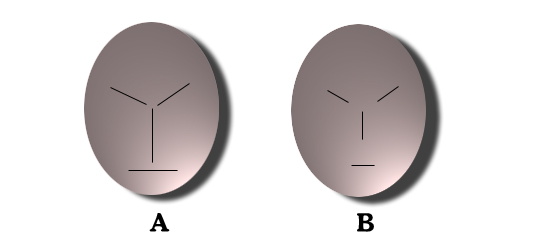

For example,

different lengths and positions in line-drawing faces would give

different impressions to observers--a face that has long lines in close

proximity would seem aged, sad, and mean (see Figure 1a); a face that

has shorter, farther apart lines would seem youthful and serene (see

Figure 1b). These are the result of perceived contradictions and

expansions.

Arnheim (1974) states that these visual forces are physically and

psychologically real, not merely figures of speech. Psychologically,

the interplay of forces in a picture exists in the experience of any

person who looks at it. Since these forces have a point of attack, a

direction, and an intensity, they meet the conditions established by

physicists for physical forces (p.16).

Figure 1. A mean face and a serene face

Arnheim

adopted the assumption that human mind operates on the infrastructure

of a homeostatic equilibrium, and any stimulation from the outside or

inside of an organism will upset the balance of that basic state and

lead directly to a countermove (1988, Nov-Dec., p.588). For an

organism, pleasure results from reductions of tension

or a balance of drive. Visual pleasure works in the

same way. **

Arnheim

(1974) also uses the analogy of physics to explain the vitality of

visual forces in art. In physics the principle of entropy, also known

as the second law of Thermodynamics, asserts that in any isolated

system, each successive state represents an irreversible decrease of

active energy. The universe tends toward a state of equilibrium in

which all existing asymmetries of distribution are eliminated (p.36).

Art is but one manifestation of this universal tendency towards the

state of simplest structure in physical systems (Arnheim, 1971, p.255).

Arnheim built

his theory of visual dynamic basing upon mainly painting, sculpture and

music. He regards photography as less dynamic than these arts. The

characteristics of photography in Arnheim's theory could be described

as the following:

First, the

nature of painting does not derive from its subject matter, but from

the media in which it is created: the sheet of paper, the canvas, the

stone, and the tools and materials. On the contrary, photography

springs from the environment. Arnheim describes the difference with

this phrase: "Painting and sculpture come from the inside out;

photography comes from outside in" (Arnheim, 1986, p.115-116). We might

say that painting and sculpture are "media-driven," but photography is

"environment-driven."

As a

photographer, I believe that photography is not necessarily "outside

in." Equipped with three Nikon cameras, eight lenses, fifty filters and

some other accessories, I always take the media as the first

consideration when I decide what I will do with the subject. Basically,

all forms of art are the materialization of ideas.

In other words, all arts fall along a media-environment

continuum.

Because

Arnheim believes that photography is from the outside in, it is said to

be less expressive in the sense of containing the visual tensions of

the subject. Arnheim (1979) asserts that photography, in spite of its

authenticity, is not the best tool to enhance visual thinking; rarely

will it do the job without the help of other means such as schematic

drawings, graphs, etc. Visual education, in Arnheim's view, must be a

statement of what is happening. A sequence is shown by visible

continuity. Cause and effect are shown by an observable proximity in

time or space or both. According to Arnheim, photographs cannot show

such things as well as other media (p.148).

Aesthetical

visual forms contain directed tensions, or visual dynamic. They

represent a happening rather than a being. Thus, a good picture of

football players shows intense action, while a poor one makes the

figures look awkwardly arrested in midair (Arnheim, 1979, p.75). In

Arnheim's view, it is more likely for a painter to create visual

tensions, but for photographers, the reality of a physical subject

comprises the total course of its existence in time. To render it in

the timeless medium of painting, the artist may translate a synthesis

of the time sequence into an appropriate immobile image. For that same

image, the photographer is limited to selecting a momentary phase of

the sequence. Thus, according to Arnheim, a photograph might not carry

the most dynamic elements of that event ( 1986, p.117).

Arnheim's

opinion might be correct in regard to early photography, but today

quite a few cameras are capable of track focusing and continuous

shooting. Catching the crucial moment of an event is no longer

difficult. Moreover, even a traditional camera is able to record the

motion of an image with a long exposure. Once a photographer mounted a

Nikon N6006 on his bicycle while cycling at night. His picture reveals

a sense of time sequence, and the visual tensions are clearly displayed

through the sharp and blurred subjects.

According to

Arnheim (1979), environment-driven photography carries a property of

"natural accident." Impressionists, who were inspired by photographs,

departed from classic orderliness and stillness in their painting

styles and experimented with the composition of natural accident to

portray indifference, isolation and unawareness. Nonetheless, the

so-called accident was the intent of the artists and under their

control.

However,

Arnheim does not consider natural accident in photography as

successfully controlled as it is in Impressionist paintings.

Photography introduces accident into every one of its products. A photo

is never more than partially comprehensive to the human eye. Therefore,

as a medium of art, photography will always suffer from the inherent

compromise, Arnheim argues (p.170).

Because

photography is said to be environment-driven, Arnheim (1986) considers

it an art of particularity rather than an expression of universality.

He asserts that painters are inclined to start from a highly abstract

level and would reach individuality only by special elaboration.

Photography, on the other hand, would have a hard time presenting an

abstraction. Instead of stating abstractness positively, it can only

arrive at it negatively, by eliminating some of the primary data

(p.116).

In

photography, the detailed rendering of an individual human body is

common. A normally focused shot of a human body displays all the

imperfections of the model, unless the photographer searches for the

rare specimen of perfection such as a glamorous young woman or a

well-built athlete. These images are ideals, like their counterparts in

painting and sculpture, but given the difference in medium, their

connotation is not the same. Arnheim says:

The photographic documents are

not the creations of an idealizing imagination that responds to the

imperfections of reality with a dream of beauty. Instead, they are the

trophies of a hunter who looks for the unusual in the world of what

actually exists and discovered something exceptionally good. (1986,

p.121)

Furthermore,

since photographs are reproductions of what really happened in a

particular time and space, they are not self-explanatory. Their meaning

depends on the total context of which they are a part. When photography

wishes to convey a message, it must try to place the image into the

proper context. Usually this will require the help of the written or

spoken word (Arnheim, 1986, p.119).

John Berger

also states that photography is an art of "ambiguity." Without the aid

of captions, the audience always interprets photos in a way that is

completely different from what they really are or what they originally

mean. I totally agree with Arnheim that photography is an art of

particularity rather than universality. Again taking the human figure

as an example, the nude photos of Man Ray and Alfred Stiegitz are quite

different. The nudes in Man Ray's album are expressed in the European

style while the latter ones are American. Perhaps Ray and Stiegitz did

not deliberately embody their arts in certain cultural styles, but the

women in their pictures definitely carry those particular traits.

Arnheim

(1979) considers photography an improper medium to express a person's

personality. He has said:

The presence

of a portrait photographer's camera tends to paralyze a person's

expression, so that he becomes self-conscious, inhibited, and strikes

an unnatural pose. Candid shots are momentary phases isolated in time

and space from the action and setting of which they are a part.

Sometimes they are highly expressive and representative of the whole

from which they are taken. Frequently, they are not. Furthermore, the

angle from which a shot is made, the effect of lighting on shape, the

rendering of brightness and color values, as well as modifications

through retouching, are factors that make it impossible to accept a

random photograph as a valid likeness. (p.55)

This argument

puzzles me. On one hand, Arnheim criticizes photography for lacking

visual dynamic and carrying disorganized natural accident because it is

from "outside in" and the manipulation of media is not sufficient. On

the other hand, he says that photography cannot truly express a

person's essence because it has too much artist intervention and

manipulation. It seems to be contradictory. Actually, artificial

procedures in photography such as switching angles and retouching might

contribute to a valid likeness. Furthermore, psychologists generally

agree that one's personality is situational rather than stable. It is

doubtful that we can find one "right" representation of anyone's

personality. On one occasion perhaps a snapshot of a natural accident

shows an expressive gesture of a person vividly, but at another time a

picture taken in a studio setup may manifest his/her essence clearly.

Sometimes a painter can reveal the very nature of a person in a

particular situation, but a photographer might handle this job better

under another circumstances.

When such a prominent

psychologist of art as Arnheim is so critical of photography, it is no

wonder that even now photography is not highly regarded as a type of

fine art. Nonetheless, we should not fully accept his theory without

careful examination. His theory of visual dynamic is based on the

assumptions of homeostatic equilibrium and entropy, which are believed

to be universal principles in the human world and the universe.

However, I wonder whether visual forces as a major criterion in art is

universal or cultural. I agree with Arnheim that photography is an art

of particularity, but this doesn't mean that photography must be from

"outside in." In Arnheim's theory, if photography has too much natural

accident, it will hardly carry visual dynamic. But if it has too much

photographer intervention and manipulation of the subject, it will

paralyze the expression of the subject's essence. Perhaps it is the

photographer's mission to strive for a balance between these tensions.

Notes

* Although

Arnheim's theory is so insightful as to point out the inadequacy of

verbal cognition, the dichotomy of visual thinking and verbal thinking

still oversimplifies the breadth of human cognition. According to

Howard Gardner, human intelligence can be classified into seven

dimensions, namely artistic, linguistic, kinesthetic, mathematic,

musical, interpersonal and intrapersonal (Gardner, 1991). I believe

that this is a more comprehensive approach to look at human cognition.

In addition,

it is debatable whether visual thinking is the highest form of

cognition. Albert Bandura (1986) insists that mental image and verbal

memory are interrelated but most of our information is stored in verbal

form (p.58). Jean Piaget asserts that the development of human

cognition progresses from the dependence on sensory input to the

dependence on concepts (cited in Hergenhann, 1988, pp.271-288). Some

psychologists distinguish field dependent from field independent

thinkers. Field dependence refers to cognition based upon a

clearly-defined visual object, while field independence is defined as

perception without distraction or confusion by the environment.

Interestingly enough, field independence is considered the higher

cognitive skill of the two (cited in Hettinger, 1988). In short, it is

doubtful that the inference that visual sense is the highest form of

cognition would be supported by most psychologists.

** The model

of homeostatic equilibrium was also accepted by Sigmund Freud and

Edward Hull. Today this model is no longer popular in psychology

because psychologists found that theories of Freud and Hull are hardly

applicable to the real world. It is no guarantee that we can maximize

our pleasure even if we make the greatest effort to reduce tensions.

John Atkinson (1965) classifies personality traits into two categories,

namely tendency to succeed and tendency to avoid failure (p.73). For

the former, tensions might be a source of pleasure!

Regarding

visual arts, Oriental paintings, in value contrast, color hues and

composition, are often less tensed than their Western counterparts. I

doubt that visual tensions as the major criterion in art is universal.

Arnheim, R.

(1969). Visual thinking. Los Angeles, CA:

University of California Press.

_____.

(1971). Entropy and art: An essay on disorder and order.

Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

_____.

(1974). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the

creative eye. Los Angeles, CA: University of California

Press.

_____. (1979)

Toward a psychology of art. Los Angeles, CA:

University of California Press.

_____.

(1986). New essays on the psychology of art. Los

Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

_____. (1988

Nov.-Dec.). Visual dynamics. American Scientist, 6,

585- 591.

Atkinson, J.

W. (1965). The mainsprings of achievement oriented activity. In J. D.

Krumboltz (Ed.), Learning and the Educational Process (pp.25-38,

48-66). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Behrens, R.

(1998). Rudolf Arnheim: The little owl on the shoulder of Athene. Leonardo,

31, 231-233.

Gardner, H.

(1991). Multiple intelligences: Theory and practice.

New York: Basic Books.

Hergenhann,

B. R. (1988). An introduction to learning theories.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hettinger, G.

(1988). Operationalizing cognitive constructs in the design

of computer-based instruction. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana

State University Press.

Verstegen, I.

(1996). The thought, life, and influence of Rudolf Arnheim. Genetic,

Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 122, 197-214.

Copyright ©

Navigation