|

|

The triple alliance among art,

ethics and politics:

A tension between universal communicability and fleeting political

views

(2007, Winter) BAP Quarterly, 3(8)

|

|

Introduction

Should ethical values play a role in aesthetical judgment? This topic has been

hotly debated among philosophers of art, artists, art historians, and art

critics for a long time. Although Gaut (2001) declared that ethicism, which

asserts that aesthetical values of art are dependent on whether the message

embedded in the work is morally right or wrong, has won in the long debate

over art and ethics. I, however, think that this issue is far from reaching a

conclusive closure. It is not the intention of this essay to resolve this

question once and for all. Neither will it pour new wine into the old bottle.

Rather, this article is a humble attempt to give some thoughts for artists and

art critics to consider.

Granted that moral goodness or badness of certain works of art would affect

their aesthetical quality, but is it always the case that this kind of

ethical-aesthetical association is influenced by one’s political orientation?

The term “triple alliance” in the title does not imply that art, ethics, and

politics always go together. While ethical judgments are not necessarily

political judgments, political views expressed in art always carry a strong

moral undertone. For example, an art critic may dislike a movie for its

violent and obscene content. In this case his moral statements are not

political unless the critic relates these issues to gun control and feminist

movement. On the other hand, political statements are inevitably “moral.” In

politics the polarity of “us vs. them” can be found everywhere. It is true

that confrontations also happen outside the political domain. A quantitative

researcher and a qualitative researcher could disagree with each other, but it

is extremely rare to see one researcher to consider the other side morally

wrong rather than methodologically wrong. Similarly, we would be hard pressed

to find a Fisherian statistician call a Bayesian “evil” or vice versa.

However, usually political commentaries, no matter where they are

expressed--in words or artwork--, articulate the argument by presenting how

morally right the proponents are and how morally wrong the rivals are. If

moral values are relevant to artistic values and the ethical standard is fused

with certain political views, we should scrutinize the meanings of this triple

alliance. In scientific inquiry it is a common practice to examine many rival

models by asking “what-if” questions. By the same token, as political views

are fleeting all the time, art critics might also construct “alternate

realities” to evaluate whether the triple alliance among art, ethics, and

politics is necessary or contingent.

Images of Germany and Italy in art

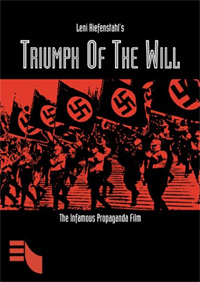

Triumph of the Will

The

example cited by Gaut to support his notion of art-ethics inter-dependence is

a political one: Leni Riefenstahl’s famous film, Triumph of the Will,

is a glowingly enthusiastic account of the 1934 Nuremberg Nazi Party rally.

Needless to say, the film is today charged as bad art because it is nothing

more than propaganda for Adolf Hitler. The case is definitely clear-cut; Nazi

Germany was defeated and its ideology was completely discredited. It is

important to emphasize that I am not a Nazi sympathizer. But just for the sake

of philosophical argument, let’s ask a question in a counterfactual manner:

What would have happened if Nazi Germany had won World War Two, or forced a

truce with the Allied powers and thus the regime had continued? Would

Triumph of the Will still be considered poor art? The

example cited by Gaut to support his notion of art-ethics inter-dependence is

a political one: Leni Riefenstahl’s famous film, Triumph of the Will,

is a glowingly enthusiastic account of the 1934 Nuremberg Nazi Party rally.

Needless to say, the film is today charged as bad art because it is nothing

more than propaganda for Adolf Hitler. The case is definitely clear-cut; Nazi

Germany was defeated and its ideology was completely discredited. It is

important to emphasize that I am not a Nazi sympathizer. But just for the sake

of philosophical argument, let’s ask a question in a counterfactual manner:

What would have happened if Nazi Germany had won World War Two, or forced a

truce with the Allied powers and thus the regime had continued? Would

Triumph of the Will still be considered poor art?

Schindler’s List

Interestingly enough, anti-Nazi movies are considered inappropriate for

different political reasons in different national contexts. For example,

Schindler’s List directed by Steven Spielberg in 1993 presents the true

story of Nazi party member Oskar Schindler who saved over 1,100 Jews from

concentration camps during the Holocaust. Who can argue against the moral

goodness of this film? Indeed, the movie was not welcome in several Islamic

countries, and Malaysia banned it for alleging it as Zionist propaganda,

evidenced by its depiction of the Jews as “stout-hearted” and “intelligent”

(New York Times, 1994). In the eyes of Malaysian Muslims, perhaps

Schindler’s List could even be morally and aesthetically equated with

Triumph of the Will. Consider this thought experiment: Had Israel never

established a nation in 1948, would the movie be universally accepted as a

masterpiece today?

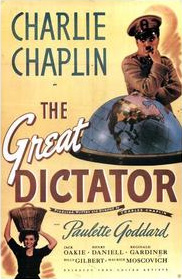

The Great Dictator

Before the Axis of power was destroyed, artworks portraying Germany and Italy

in a negative fashion were a taboo. When Charlie Chaplin announced his plan in

1939 to make the movie The Great Dictator, which is a mockery of Adolf

Hitler, the British government tried to persuade him to cancel the project,

because the government was afraid that this insulting film would antagonize

Hitler and provoke further confrontation between England and Germany.

Similarly, today any satirical movie of Kim Jong Il might be considered

sensitive and even damaging. In spite of the pressure, Chaplin went on to

produce The Great Dictator and released the film in 1940. But on the

other side of the Atlantic Ocean, several Chicago theaters refused to show

this movie because it might enrage the German population in Illinois. American

Communist movement also denounced the film as Stalin had signed the

non-aggression pact with Hitler before the release of the film (Malan, 1989).

But after the Soviet Union, the Great Britain, and the United States joined

hand in hand to fight the Nazis, suddenly the movie was highly regarded. It

was shown in London during the Battle of Britain for boosting morale. General

Eisenhower asked the French ally to dub films acted by Chaplin for

distribution in France after France was liberated. No doubt today The Great

Dictator has elevated to the status of seminal classic. It is true that

none of the initial rejections of The Great Dictator is based upon

aesthetics. But is it fair to say that to some extent subsequent and current

aesthetical praises of this Chaplin movie can be attributed to its moral

righteousness, which is tied to its once unpopular political view? How would

have been this movie received in the American context if the US did not enter

WWII? Before the Axis of power was destroyed, artworks portraying Germany and Italy

in a negative fashion were a taboo. When Charlie Chaplin announced his plan in

1939 to make the movie The Great Dictator, which is a mockery of Adolf

Hitler, the British government tried to persuade him to cancel the project,

because the government was afraid that this insulting film would antagonize

Hitler and provoke further confrontation between England and Germany.

Similarly, today any satirical movie of Kim Jong Il might be considered

sensitive and even damaging. In spite of the pressure, Chaplin went on to

produce The Great Dictator and released the film in 1940. But on the

other side of the Atlantic Ocean, several Chicago theaters refused to show

this movie because it might enrage the German population in Illinois. American

Communist movement also denounced the film as Stalin had signed the

non-aggression pact with Hitler before the release of the film (Malan, 1989).

But after the Soviet Union, the Great Britain, and the United States joined

hand in hand to fight the Nazis, suddenly the movie was highly regarded. It

was shown in London during the Battle of Britain for boosting morale. General

Eisenhower asked the French ally to dub films acted by Chaplin for

distribution in France after France was liberated. No doubt today The Great

Dictator has elevated to the status of seminal classic. It is true that

none of the initial rejections of The Great Dictator is based upon

aesthetics. But is it fair to say that to some extent subsequent and current

aesthetical praises of this Chaplin movie can be attributed to its moral

righteousness, which is tied to its once unpopular political view? How would

have been this movie received in the American context if the US did not enter

WWII?

A Farewell to Arms

Before the breakout of World War Two, it was also politically incorrect to

insult Italy. In Hemingway’s novel A Farewell to Arms, Italy was

presented in a non-desirable fashion. Before World War I, Italy was an ally of

Germany and Austria. However, the Allies lured Italy to switch sides by

promising Italy the land it had requested from Austria. In return to the

promised reward, the mission of Italy's army was to hinder the Austrian troops

from helping the Germans in France. But since Italian army was ill equipped,

the battle caused the death of 500,000 Italian soldiers in 1916 alone. This

was the setting of A Farewell to Arms. In 1929 Italy banned the novel

due to its account of the disastrous Italian retreat following the Battle of

Caporetto. Americans did not take this insult to their ally in World War I

lightly. In the same year five issues of Scribner’s Magazine were

prohibited to be sold in Boston because they printed the story of A

Farewell to Arms (Haight, & Grannis, 1978). Needless to say, during and

after World War II the American view of A Farewell to Arms made a

180-degree turn-around. However, had Italy switched sides again in World WarII,

would this novel still have been considered politically incorrect? Before the breakout of World War Two, it was also politically incorrect to

insult Italy. In Hemingway’s novel A Farewell to Arms, Italy was

presented in a non-desirable fashion. Before World War I, Italy was an ally of

Germany and Austria. However, the Allies lured Italy to switch sides by

promising Italy the land it had requested from Austria. In return to the

promised reward, the mission of Italy's army was to hinder the Austrian troops

from helping the Germans in France. But since Italian army was ill equipped,

the battle caused the death of 500,000 Italian soldiers in 1916 alone. This

was the setting of A Farewell to Arms. In 1929 Italy banned the novel

due to its account of the disastrous Italian retreat following the Battle of

Caporetto. Americans did not take this insult to their ally in World War I

lightly. In the same year five issues of Scribner’s Magazine were

prohibited to be sold in Boston because they printed the story of A

Farewell to Arms (Haight, & Grannis, 1978). Needless to say, during and

after World War II the American view of A Farewell to Arms made a

180-degree turn-around. However, had Italy switched sides again in World WarII,

would this novel still have been considered politically incorrect?

Cases in American movies

The Spirit of 1776

Next, consider two movies made in the United States during the early 20th

century. In 1917, with all good intentions a German-Jewish immigrant named

Goldstein produced a movie entitled The Spirit of 1776 as paying

tribute to the founding fathers of America. It is logical to think that no one

could dispute the ethical goodness and politically correctness of this movie.

However, Goldstein made a fatal mistake by demonizing the British Empire when

America decided to give a hand to England in fighting against Kaiser’s

Germany. President Wilson banned the film using the Sedition Act as his legal

base. In support of the seizure of the film, Judge Beldsoe wrote, “History is

history and fact is fact . . . the United States is confronted with . . . the

greatest emergency . . . [its] history. There is now required . . . the

greatest devotion to a common cause . . . this is no time . . . for souring

dissension among [the] people, and of creating animosity . . .[with the]

allies.” Goldstein was arrested and convicted of espionage in having attempted

to incite a mutiny of the U.S. Armed Forces (Collins, 2001). Had Mel Gibson

acted in Patriots in 1917 or 1941, would he have been another Robert

Goldstein?

The Birth of a Nation

Unlike The Spirit of 1776, in 1915, another movie entitled The Birth

of a Nation, directed by D.W. Griffith and aimed to promote American

cultural heritage, received a much nicer treatment. By today’s standard, this

movie is far more ethically and politically controversial than The Spirit

of 1776. Although the film is highly ranked in the US film history for its

technical innovations, it is clear that the message of the film has strong

elements of white supremacy. However, over the next twenty years The Birth

of a Nation became one of the most admired and profitable films ever

produced by Hollywood until it was dethroned by Gone with the Wind in

1940. In 1992 the United States Library of Congress deemed it “culturally

significant” and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry

(Lang, 1994; Michele, 2003). If the film had offended one of key allies of

America rather than “Negros,” could it have easily gotten away with

such a portrayal? Unlike The Spirit of 1776, in 1915, another movie entitled The Birth

of a Nation, directed by D.W. Griffith and aimed to promote American

cultural heritage, received a much nicer treatment. By today’s standard, this

movie is far more ethically and politically controversial than The Spirit

of 1776. Although the film is highly ranked in the US film history for its

technical innovations, it is clear that the message of the film has strong

elements of white supremacy. However, over the next twenty years The Birth

of a Nation became one of the most admired and profitable films ever

produced by Hollywood until it was dethroned by Gone with the Wind in

1940. In 1992 the United States Library of Congress deemed it “culturally

significant” and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry

(Lang, 1994; Michele, 2003). If the film had offended one of key allies of

America rather than “Negros,” could it have easily gotten away with

such a portrayal?

Discussion

At first glance, the above examples seem to promote some form of relativism or

to dissociate political views from moral judgment, and thus deny ethicism.

Actually, it is beyond dispute that Holocaust, Nanking Massacre, Gulag, and

Red Khmer are absolute evils, and any artworks that glorify these crimes

should never be artistically appreciated. However, please keep in mind that

people affirm their final judgment long after the dust has settled. But in

1934 could Leni Riefenstahl foresee the Holocaust and World War II while

making The Triumph of the Will? In 1939 when the Soviet Union and the

Nazi Germany were at peace, how could Communists endorse The Great Dictator?

As a fallible human being, I regard the entanglement of artistic, ethical, and

political elements as a risky enterprise. In one of the current exhibitions

entitled “Defining moments in Photography, 1967-2007” held in the Museum of

Contemporary Art, Chicago, Robert Heinechen’s photograph Pinup taken in

1968 is included as one of the most important photographic artworks during the

last twenty years. Robert Heinechen was a jet pilot but became an anti-war

activist after leaving the service. In Pinup, a half-naked woman and a

newspaper showing a headline “Ten Southmen killed in action” are superimposed.

This disturbing image, blending death and sexuality, conveys a forcefully

moral and political message that American men were exploited by the government

while women were exploited by pornography. Unlike World War II, the Cold War

did not end with a decisive victory favoring America. The Soviet Union

collapsed and the Berlin Wall was dismantled, yet Vietnam, Cuba, and North

Korea still existed though Vietnam has transformed its economy from central

planning to market-driven capitalism. However, if half a century from now the

Vietnamese regime had ceased to exist and historians made a 180-degree turn

about the Vietnam War, could Pinup remain in the list of defining

moments in photography? While I wholeheartedly consider Ansel Adam’s photos of

nature’s beauty timeless, I have reservations about Heinechen’s work. As a fallible human being, I regard the entanglement of artistic, ethical, and

political elements as a risky enterprise. In one of the current exhibitions

entitled “Defining moments in Photography, 1967-2007” held in the Museum of

Contemporary Art, Chicago, Robert Heinechen’s photograph Pinup taken in

1968 is included as one of the most important photographic artworks during the

last twenty years. Robert Heinechen was a jet pilot but became an anti-war

activist after leaving the service. In Pinup, a half-naked woman and a

newspaper showing a headline “Ten Southmen killed in action” are superimposed.

This disturbing image, blending death and sexuality, conveys a forcefully

moral and political message that American men were exploited by the government

while women were exploited by pornography. Unlike World War II, the Cold War

did not end with a decisive victory favoring America. The Soviet Union

collapsed and the Berlin Wall was dismantled, yet Vietnam, Cuba, and North

Korea still existed though Vietnam has transformed its economy from central

planning to market-driven capitalism. However, if half a century from now the

Vietnamese regime had ceased to exist and historians made a 180-degree turn

about the Vietnam War, could Pinup remain in the list of defining

moments in photography? While I wholeheartedly consider Ansel Adam’s photos of

nature’s beauty timeless, I have reservations about Heinechen’s work.

Being partially inspired by Kant (Allison, 2001), I treat contentment in the

beautiful as a disinterested and free satisfaction. To be specific, our liking

of art, if it is to be aesthetical, must be free from all interests, including

political interests. If we look at art aesthetically, we should not want to

know whether anything depends or can depend on the existence of thing either

for ourselves or for any one else. Further, an aesthetical judgment is a

judgment without a concept, especially political ideology. When we find an

object beautiful, we need no definite concept or rule of it. Moreover, some

Kantians are opposed to the distraction by emotion of an art. What those

Kantians looks for in an aesthetically valuable object is universal

communicability, regardless of whether one is a capitalist, a communist, a

Jew, a Christian, a Muslim, an American, a German, or a Chinese. It does not

mean that every one must agree that the object is beautiful; instead, the

particular judgment invites universal assent: it claims that every one ought

to give his approval to the object in question and also describe it as

beautiful. It presupposes a “common sense”—the state of mind resulting from

the free play of our cognitive powers and imagination. If readers object to

the preceding idea, it is fine. We are aesthetically, epistemologically, and

methodologically different, not morally different.

References

Allison, Henry E. (2001). Kant's theory of taste: a reading of the Critique of aesthetic judgment. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Collins, John. (2001). The tragic odyssey of Robert Goldstein. Retrieved from

http://www.angelfire.com/bc/RPPS/revolution_movies/golstn.htm

Guat, Berys. (2001). Art and ethics. In Berys Gaut & Dominic Mclver Lopes (Eds.),

The Routledge companion to aesthetics (pp. 341-351). New York: Routledge.

Haight, Anne Lyon, & Grannis, Chandler B. (1978). Banned Books 387 B.C. To 1978 A.D. New York: R.R. Bowker Co.

Lang, Robert (Ed.). (1994). The Birth of a nation: D.W. Griffith, director. N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Michele, Faith Wallace. (2003). The good lynching and "The Birth of a Nation": Discourses and aesthetics of Jim Crow,

Cinema Journal 43, 85-104.

Maland, Charles J. (1989). Chaplin and American culture: The evolution of a star image. New Jersey: Princeton.

New York Times. (1994). Muslims only lose with 'Schindler' Ban.

Navigation

|